Sculpting the Physical and Absent Body

RMIT School of Art

Master of Fine Art (MC266)

THEMES IN CONTEMPORARY CREATIVE PRACTICE A

Assignment 3 - Project Report

S3836081 Jiayi Liu (Liu)

Introduction

This project explored how combining a physical sculpture with digital media can express the sensory distortions of a trauma-altered body. By projecting animation onto the sculpture, I brought the visible, external body and the invisible, internal pain into the same frame, visualising the sensations I experience as a person living with chronic pain. The project built on the original outline for a hybrid digital–physical sculpture, but during the making process, the medium shifted: instead of 3D printing and augmented reality, I created a hand-built sculpture paired with 2D animated projection to emphasise the tension between what is materially present and what is only felt.

Objectives

To materialise a trauma-altered body using abstract forms that speak to affect and embodiment rather than likeness.

To test with how digital media can encode sensations in the body such as throbbing, lingering, spreading or sudden pain.

To challenge trauma narratives that prioritise visible wounding, instead centre internal and invisible experiences.

Methods, Mediums and Formats

Hand built Sculpture

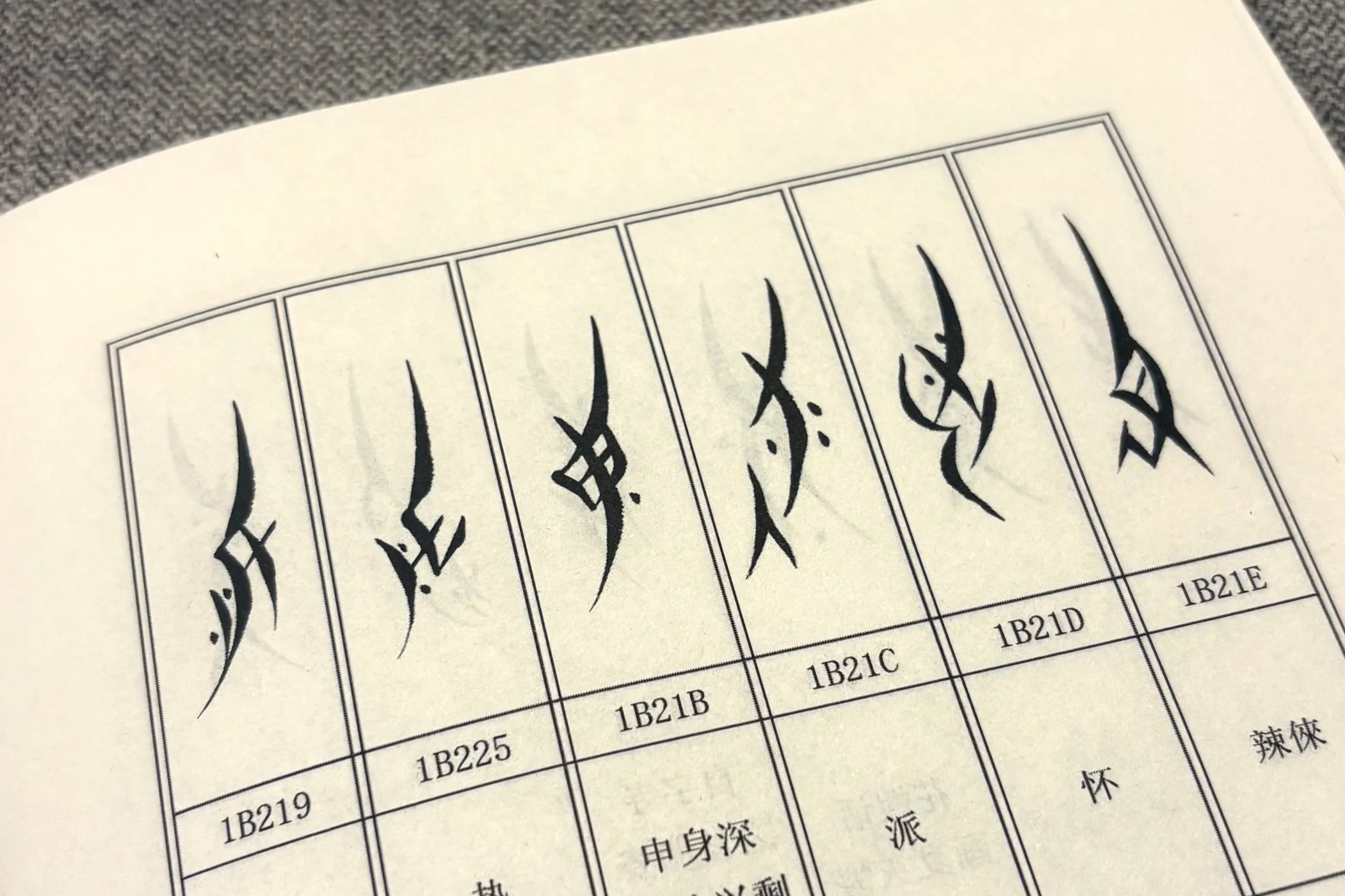

During my research, I encountered a book introduced Nüshu - a writing system created and used by women in China during the Qing Dynasty that means “women’s script.” The visual quality of Nüshu echoes my use of structures in sculptures, and its role as a secret language connects to my focus on hidden bodily trauma. Therefore, I created a sculptural form based on the Nüshu character for “Body“ with various materials. The sculpture is painted all white for projection, and applied felt onto the surface while sealing with epoxy resin to create wound-like textures.

The third one from the left is the character represents Body.

女书-规范字书法字帖 (Nüshu – Standard Script Calligraphy Copybook)

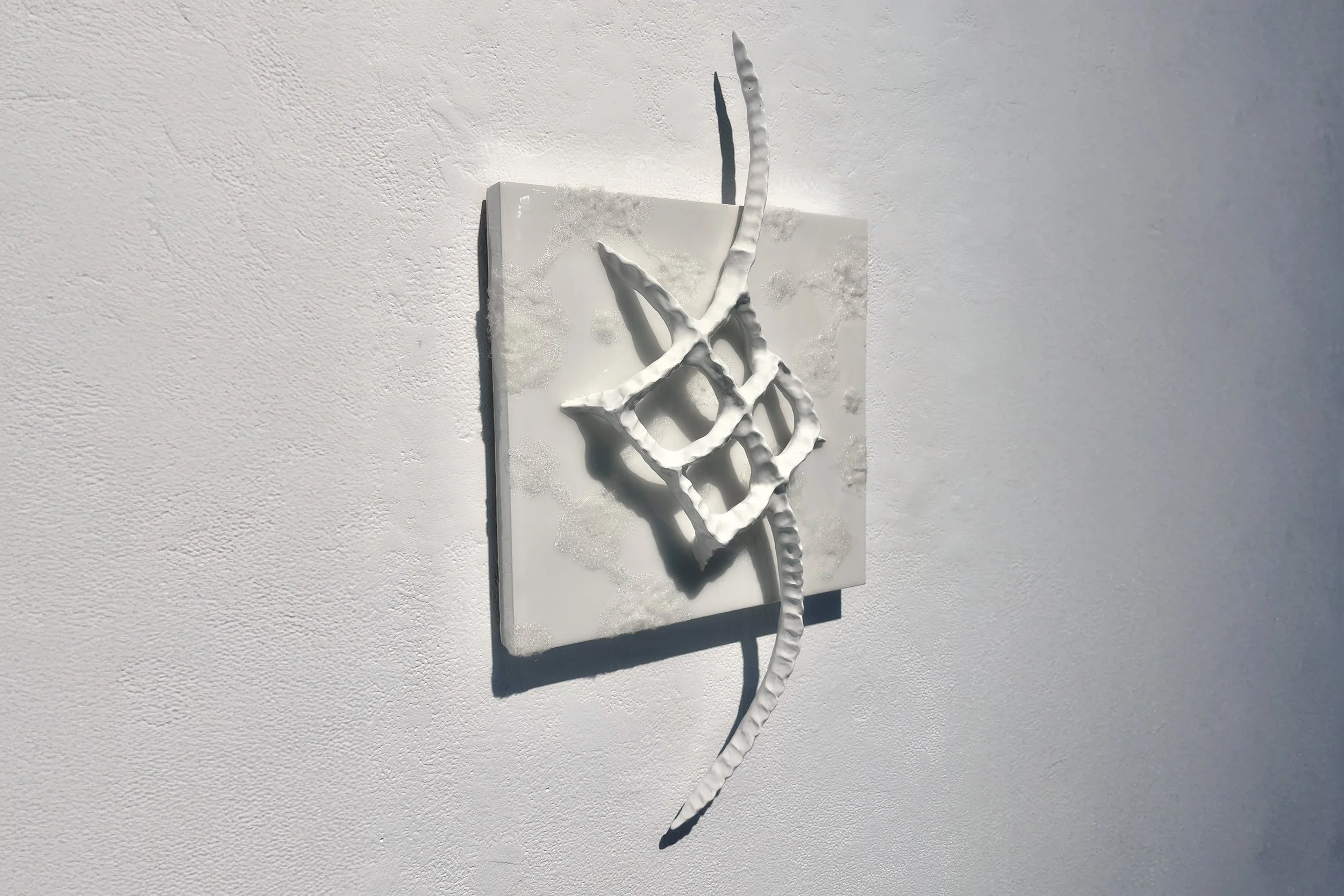

Form construction using felt board, wire, tinfoil, and epoxy clay.

Mount the finished form to a square wooden frame with E6000, spray the entire piece white, seal the paint with epoxy resin, then lay felt over the board surface while the resin is still wet.

Wall-mounted sculpture and details.

Wall-mounted sculpture.

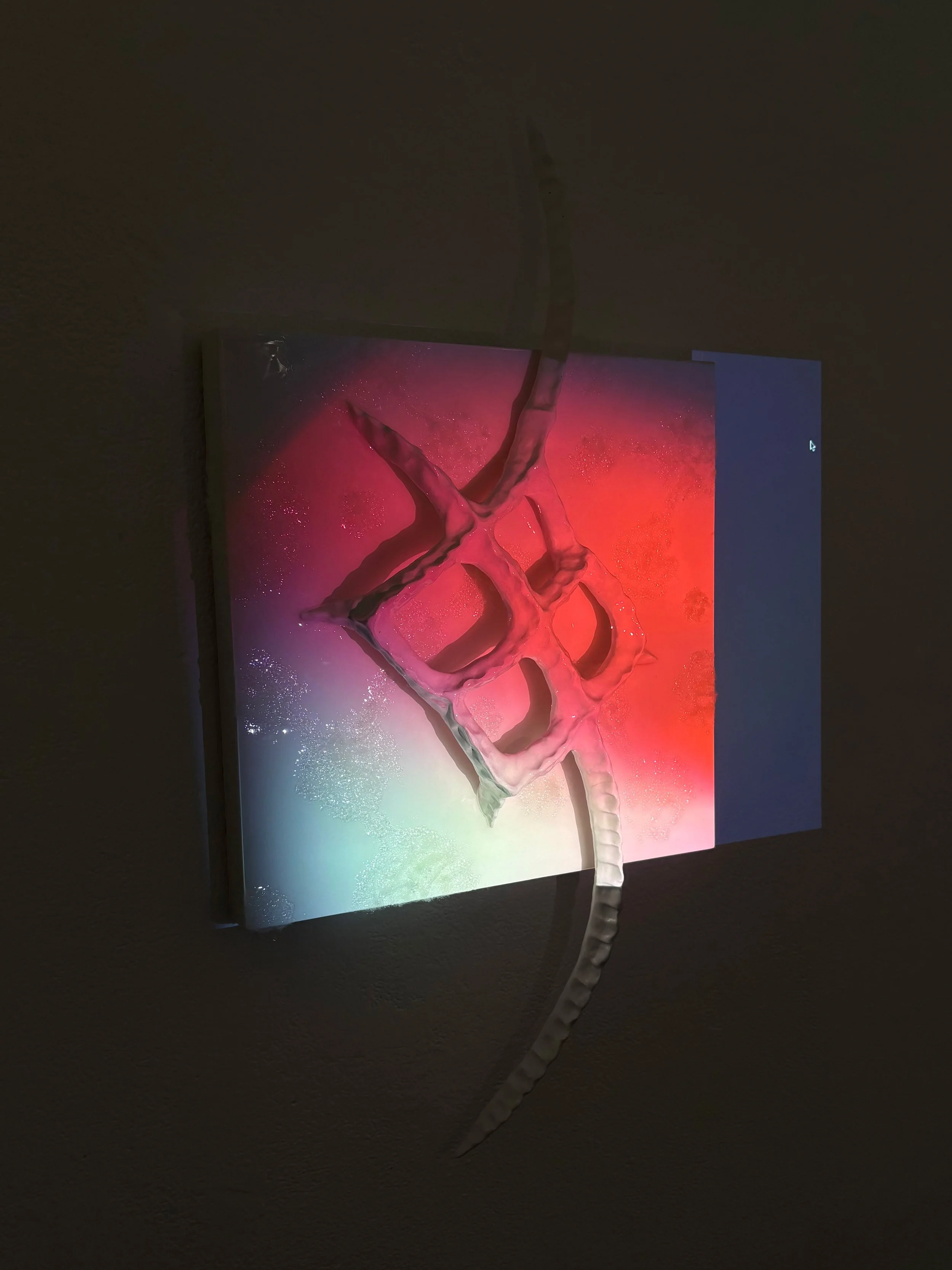

Animation

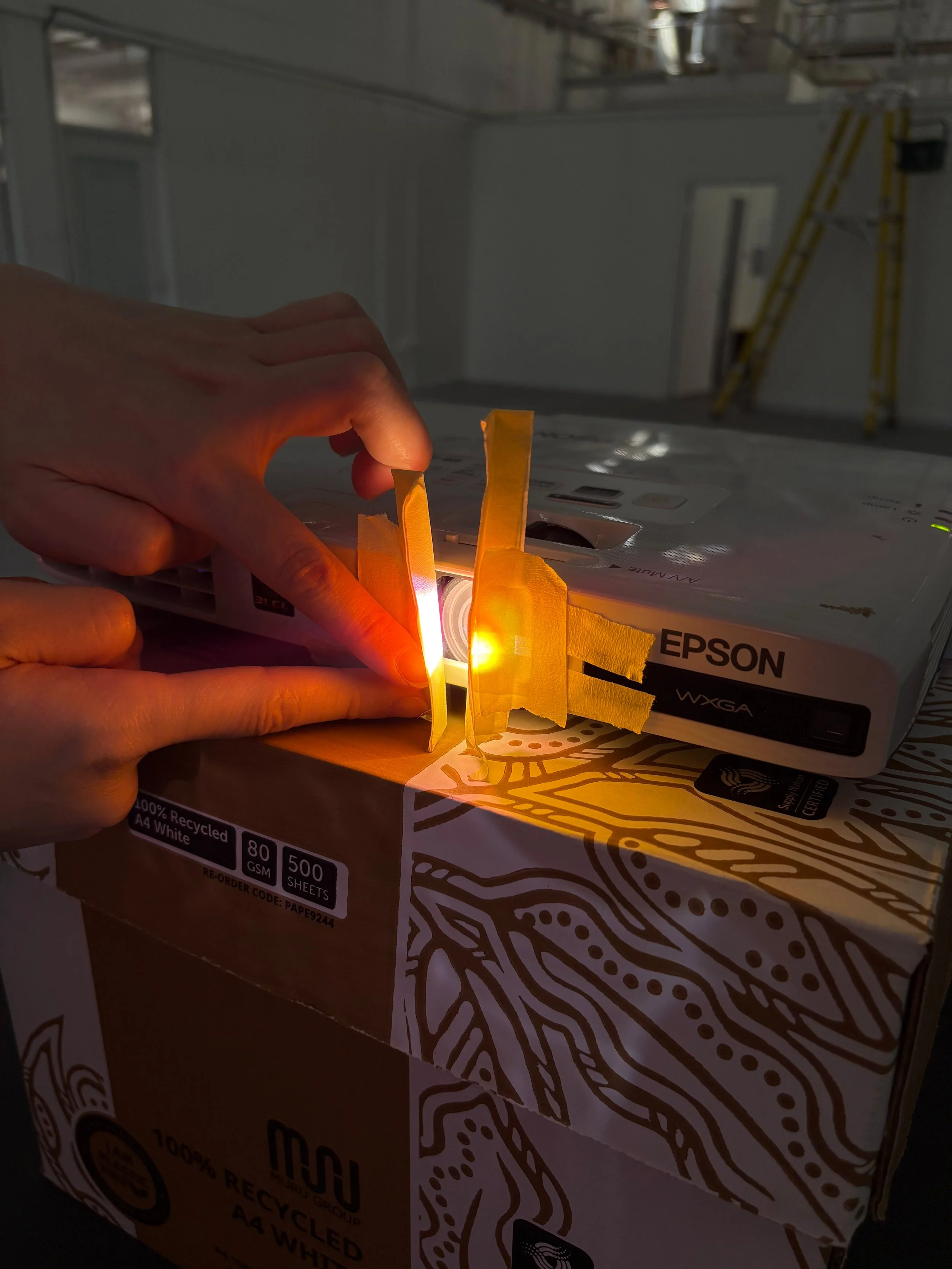

Due to my laptop’s limited capacity for 3D modelling, I shifted to After Effects for 2D animation. Using online tutorials and self-directed exploration, I created animation using colors and abstract shapes to express different kinds of pain I experienced in my body. I first produced a short animation, using a projection borrowed from friends and trialed the projection on a wall to assess feasibility. The test worked well, so I proceeded to create the full 40 seconds animation. The visual design of the animation is inspired by Elaine Scarry’s argument in The Body in Pain that bodily pain, occurring within one’s interior, can appear as remote and inaccessible to others as distant interstellar events (Scarry 1985, 3–4).

Animation editing in After Effects

Projection test onto the wall

Full animation

Site & Installation

I wanted the piece to sit within a gallery environment, so I chose the Gossard Space (Building 49) for installation.

Test projection failed to yield a clean, square frame.

Using tape to mask the sides and square the projection.

Final projection setup

Final Outcome

Real-time video documentation of animation projected onto a wall-mounted sculpture at The Gossard Space.

Digital composite: animation layered on a sculpture photograph (no live projection).

Reflection

This project brought many challenges, and I learned a lot by solving them. I followed a practice-led method where I learn by making and testing. I first planned a 3D-print/AR work, but I changed to a hand-built sculpture with 2D projection due to hardware limitations. I also did not plan to use felt, but testing felt with epoxy resin worked well and created wound-like textures. It was my first time using epoxy resin and I learned to warm the bottles in hot water before use so the hardener activates and the resin cures properly.

This was also my first time combining a handmade sculpture with digital projection. It opened a new path for mixed media, bridging traditional sculpture and technology. Animation adds motion and holds attention longer than a static object. It also fits the theme of pain well, where pain changes over time, which is expressed well with animation.

I noticed a difference between seeing the projection with my eyes and recording it on camera. The camera often shifts colour and lowers saturation. In future projects, I will learn more filming settings to better reproduce the animation. I also learnt that animation needs more editing and render time than I expected, so I will plan a longer timeline for animation next time.

Community of Practice

This project belongs to a community that links material-based sculpture, moving-image installation, and disability/trauma studies. I employ a practice-led methodology where making and experimentation are the main ways I develop ideas and outcomes.

Conceptually, I draw on frameworks of embodied-trauma and affect theory, where matter and feeling as working together rather than acting as simple signs (Ahmed 2004). Because pain and other sensations are often invisible, disability and trauma studies ask for forms that make such experiences perceptible. My approach brings the external body (the sculpture) and internal sensation (the projection) into one field of view. This follows Scarry’s point that pain resists language and needs others forms of expression (Scarry 1985). The mix of sculpture and projection also echoes Haraway’s cyborg figure and shows how technology can become part of how a body feels and communicates (Haraway 1991).

Artistically, I connect with practices that explore the body and trauma through affective materials and with works that merge objects and projection. Louise Bourgeois and Eva Hesse show how tactile structures can carry psychological and bodily states without relying on figuration. Mike Kelley uses soft and rough materials to speak to memory and emotion. Tony Oursler projects moving images onto objects to make the surface feel alive. In my work, I adapt this strategy by projecting abstract colour and shape to express bodily sensations, rather than depicting fragmented body parts like Oursler.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara. 2004. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Haraway, Donna J. 1991. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge.

MoMA. “Eva Hesse, Untitled, 1966.” MoMA (website). Accessed 18 August 2025. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81239?artist_id=2623&page=1&sov_referrer=artist.

MoMA. “Mike Kelley’s Deodorized Central Mass with Satellites.” MoMA (website). Accessed 19 August 2025. https://www.moma.org/calendar/galleries/5663.

My Art Broker. “Louise Bourgeois: The Woman Behind the Spider Sculptures.” My Art Broker (website). Accessed 18 August 2025. https://www.myartbroker.com/artist-louise-bourgeois/articles/louise-bourgeois-woman-behind-spider-sculptures.

Scarry, Elaine. 1985. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tony Oursler. “Thought Forms.” Tony Oursler (website). Accessed 19 August 2025. https://tonyoursler.com/thought-forms-newyork.

Zhao, Liming, and Xu, Yan, eds. 女书:规范字书法字帖. (Nüshu – Standard Script Calligraphy Copybook) Beijing, China: Tsinghua University, 2017.